Yesterday I posted the first part of a two-part interview with Colleen Fitpatrick, a forensic genealogist. In that interview, we discussed Colleen’s participation in a project to identify the remains located at a military crash site from 1948.

Today, we discuss her work on identifying the Titanic’s Unknown Child, among other projects.

The Genetic Genealogist:Â On April 17, 1912, two days after the RMS Titanic sank in the North Atlantic, the salvage vessel Mackay Bennett discovered the body of a young boy. The sailors paid for a monument, and the boy was buried in Fairview Lawn Cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia. In 2008, after an initial false identification based on dental records, the boy was identified as Sidney Leslie Goodwin. You were part of the team that identified Sidney. Can you tell us about that experience?

Colleen Fitzpatrick: In my opinion, working with the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory is the most compelling job that a genealogist can have. Our scientists and genealogists are dedicated to their research, willing to go the extra mile to get results. It is thrilling to me to be in on the development of cutting edge technology that has the potential to solve the highest profile genealogical mysteries in the world.

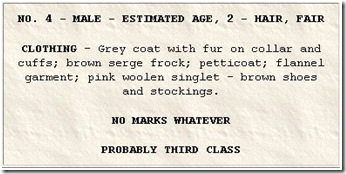

The case of the Unknown Child on the Titanic has found a niche in genealogical history. In 1912, the only clues for identifying the child were at best primitive observations (see the 1912 vintage information used to attempt an identification for the Unknown Child on the Titanic to the left) He was a male about two years old, wearing a grey coat with a brown serge frock and shoes. There was nothing out of the ordinary that might identify him as someone’s relative or friend.

The case of the Unknown Child on the Titanic has found a niche in genealogical history. In 1912, the only clues for identifying the child were at best primitive observations (see the 1912 vintage information used to attempt an identification for the Unknown Child on the Titanic to the left) He was a male about two years old, wearing a grey coat with a brown serge frock and shoes. There was nothing out of the ordinary that might identify him as someone’s relative or friend.

Almost a century later, however, our team used amazing new techniques that reached into the scraps of what was left of his body to read genetic information encoding his identity. We also had advanced knowledge about forensic dentistry at our disposal. With only three tiny teeth to work with that had survived the damp soil and acid rain of Nova Scotia for nearly a hundred years, we had all the tools we needed to restore the child’s identity to him. Sidney Leslie Goodwin is again a person, who can now speak for the dozens of children who have never been able to tell us their own stories.

And the rest is history……

TGG:Â Although you identified one of Sidney’s distant male relatives for Y-DNA testing, the article suggests that the test was halted because the mtDNA test identified the boy. Did the Y-DNA test ever proceed?

CF: When the mitochondrial DNA match was made between the remains and the Goodwin family, we no longer needed to make a Y-DNA comparison. This was a good thing. Y-DNA degrades rapidly, and there is only one Y-chromosome per cell. So our chances of harvesting enough of the right kind of Y-DNA to make an identification were low. But if we were not able to find a match using mtDNA, our only hope was to resort to using Y-DNA even if we had only a slim chance of success. Fortunately, a Y-comparison was not necessary.

CF: When the mitochondrial DNA match was made between the remains and the Goodwin family, we no longer needed to make a Y-DNA comparison. This was a good thing. Y-DNA degrades rapidly, and there is only one Y-chromosome per cell. So our chances of harvesting enough of the right kind of Y-DNA to make an identification were low. But if we were not able to find a match using mtDNA, our only hope was to resort to using Y-DNA even if we had only a slim chance of success. Fortunately, a Y-comparison was not necessary.

My Y-DNA research was important, however, because it reunited long lost Goodwin family members from Australia and New Zealand with their English and American cousins. Each of the Goodwins had a piece of their family story to share that created a more complete picture of the family tragedy. To thank me for my efforts on their behalf, the family invited me as an honorary Goodwin to the memorial they held in Halifax on August 6 for Sidney and his family.

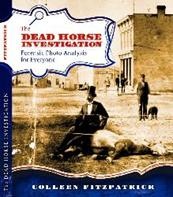

TGG:Â You recently published a new book entitled “The Dead Horse Investigation” about a recent project to identify the date of a famous photograph. Can you tell us a little more about the book?

CF:Â “The Dead Horse Investigation: Forensic Photo Analysis for Everyone” is all about identifying old photos. (See www.forensicgenealogy.info.) The name is taken from a picture that was published in the Sheboygan Daily Press a couple of years ago. It depicts a man in top hat and tails sitting on a dead horse lying at the intersection of Griffith and Indiana Avenues in Sheboygan, WI. Using every trick in the book, we were able to pin down when the photo was taken to only a handful of days in the 1870s. The only things we could not figure out were the name of the man and name of the horse.

CF:Â “The Dead Horse Investigation: Forensic Photo Analysis for Everyone” is all about identifying old photos. (See www.forensicgenealogy.info.) The name is taken from a picture that was published in the Sheboygan Daily Press a couple of years ago. It depicts a man in top hat and tails sitting on a dead horse lying at the intersection of Griffith and Indiana Avenues in Sheboygan, WI. Using every trick in the book, we were able to pin down when the photo was taken to only a handful of days in the 1870s. The only things we could not figure out were the name of the man and name of the horse.

The book contains many new ideas on how to find the who, what, when, and why of a photo, along with cases studies on how many of these ideas have been applied. The only thing the book does not cover is how to extract DNA from a photograph. We haven’t figured out how to do that yet.

TGG:Â Colleen, thank you very much for providing this information and doing this interview!

Excellent interview and one that is long overdue I might add. Colleen Fitzpatrick doesn’t get near the recognition she deserves.

Sheri Fenley

Sheri – I’m glad you enjoyed the interview. Thank you for stopping by and joining the conversation!

Have early 1900’s photo’s. My Mother pasted them to photo album black pages. How can I clean off the black paper so I can read comments left on them. Also, she never knew exactly who her father was, excepting the name Frank Miller died accidentally 1911. Have some circumstancial evidence possibilities. If your interested, we could consider the Frank Miller mystery. Thanks